A Few Weekend Thoughts On Biden's College Loan Forgiveness Program

On Wednesday of this week, President Biden issued an Executive Order to forgive some of the debt owed by those who had received college loans. In doing so, Biden was attempting to fulfill a campaign promise to forgive undergraduate student debt for people earning up to $125,000 ($250,000 for a family). “I made a commitment that we would provide student debt relief, and I’m honoring that commitment today,” he said in remarks at the White House.

According to the Office of Federal Student Aid (OFSA), an office within the US Department of Education, Biden’s plan comes in three parts. The first part extends the repayment loan pause a final time (again) to the end of 2022. Part 2 is what’s getting all the attention at the moment. It says:

To smooth the transition back to repayment and help borrowers at highest risk of delinquencies or default once payments resume, the U.S. Department of Education will provide up to $20,000 in debt cancellation to Pell Grant recipients with loans held by the Department of Education and up to $10,000 in debt cancellation to non-Pell Grant recipients. Borrowers are eligible for this relief if their individual income is less than $125,000 or $250,000 for households.

Part 3 of the President’s plan is different in that it is in the form a proposed rule “to create a new income-driven repayment plan that will substantially reduce future monthly payments for lower-and middle-income borrowers,” according to the OFSA. The proposal would:

Require borrowers to pay no more than 5% of their discretionary income monthly on undergraduate loans. This is down from the 10% available under the most recent income-driven repayment plan.

Raise the amount of income that is considered non-discretionary income and therefore is protected from repayment, guaranteeing that no borrower earning under 225% of the federal poverty level—about the annual equivalent of a $15 an hour wage for a single borrower—will have to make a monthly payment.

Forgive loan balances after 10 years of payments, instead of 20 years, for borrowers with loan balances of $12,000 or less.

Cover the borrower’s unpaid monthly interest, so that unlike other existing income-driven repayment plans, no borrower’s loan balance will grow as long as they make their monthly payments—even when that monthly payment is $0 because their income is low.

Part 3 is consequential, and the fourth bullet point of Part 3 even more so. Interest payments can easily double the size of a student loan, and anything that reduces the interest burden will reduce the size of the loan and, consequently, the time required to pay it off. But a proposed rule is not an Order and will take time before being finalized, perhaps a lot of time.

Right now we are in the knee jerk phase of this issue. Republicans categorize Biden’s move as political and unfair to those who worked hard to pay off their loans. Why should their tax dollars now subsidize the millions who haven’t? The far right, more rabid of the bunch, have been raining tweet storms condemning the very idea of forgiving the loans, all the while forgetting to mention their own Paycheck Protection Act loans, most well over $100,000, have all been forgiven.

In thinking about this, the first question one might want to ask is: Does the President have the authority to do it? House Speaker Nancy Pelosi doesn’t think so. “The president can’t do it,” she said in July. “That’s not even a discussion.”

We can expect this decision to be challenged in the courts. But, at the very least, it offers President Biden a chance to say he is honoring a commitment, a promise, even if the Judiciary ultimately won’t let him do it.

How and why has going to college come to this? I think the answer can be found in the long, winding, potholed road to higher education of the last 55 years. It’s complicated, and people have devoted entire careers to studying it.

I’m concerned, in a practical sense, with what changed from the time I and my peers affordably attended college in the late 1960s. For instance, how and in what manner have costs increased? To what degree and why is there now a far greater percentage of high school graduates attending four year, or even two-year colleges? Have wages commensurately grown with college costs to allow parents and their children to be able to afford it all? How has the for-profit boom in colleges contributed to the college loan crisis, if it has?

To begin to answer those questions, let’s first take a look at where we are now.

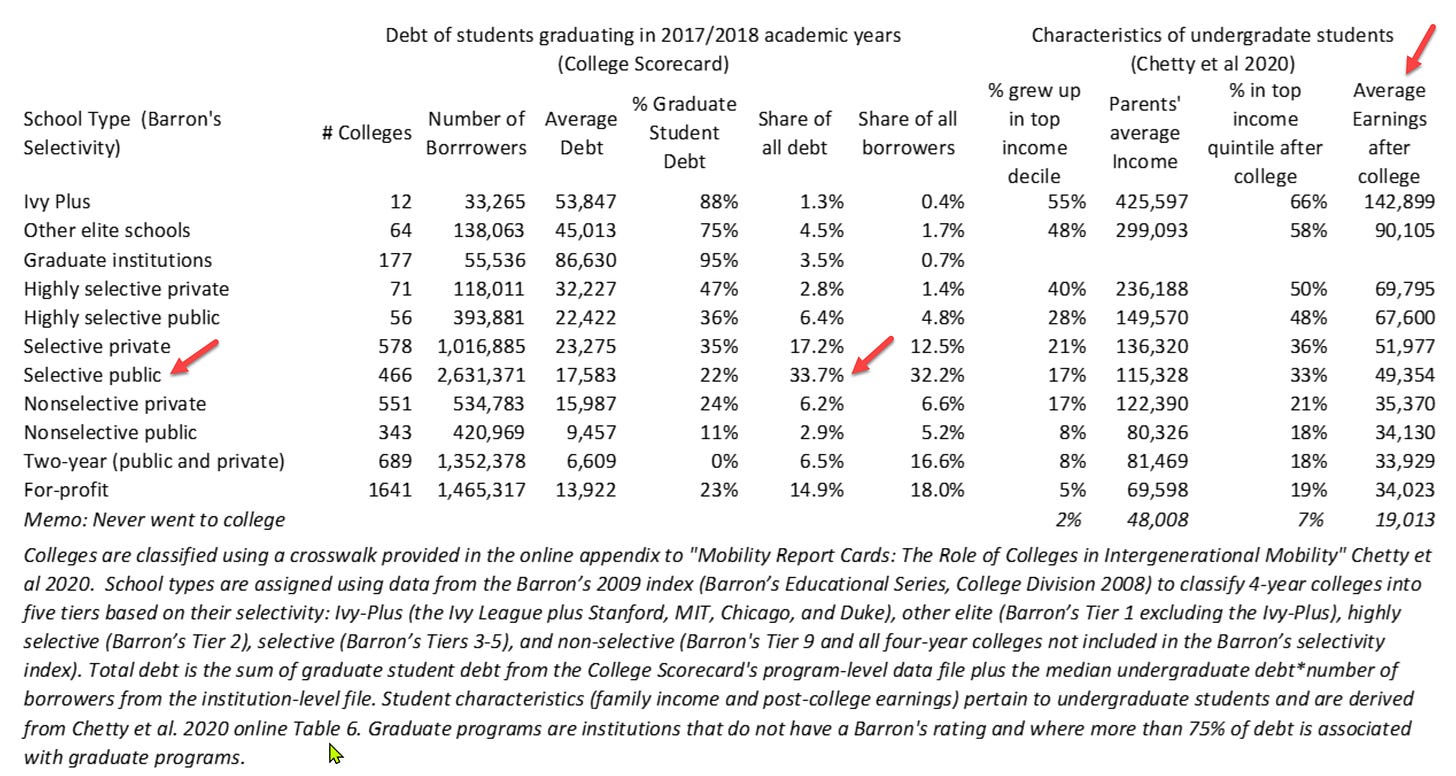

Adam Looney, the Nonresident Senior Fellow at the left-leaning Brookings Institution and the Executive Director of the Marriner S. Eccles Institute at the University of Utah, is one of our foremost experts on college loans and costs. He has argued for quite some time against across-the-board loan forgiveness, because a disproportionate amount goes to people who don’t need it, Ivy League educated doctors, lawyers, etc. He has produced the following table to demonstrate his argument. The table categorizes all colleges and graduate programs represented in the College Scorecard by their selectivity using Barron’s college rankings. The left panel of the table describes the debts owed by students at these colleges. The right panel describes their family economic background and their post-college outcomes. From top to bottom, the schools are categorized by their selectivity—how hard it is to get accepted. Note that the more selective the school, the greater the average debt (with the exception of the for-profits). The same holds true for the two far right columns. The more selective the school, the greater the after college earnings. Note also that, with the exception of the Ivy Plus graduates, the average after college earnings for every other category are less than the President’s cap of $125,000 for loan forgiveness qualification.

I’m going to ignore the harm done by for-profit colleges, except to say the largest single source of student debt in America is one of them—the University of Phoenix, the gigantic online for-profit chain. Students who graduated or dropped out in 2017-2018 owed about $2.6 billion in student loans; two years after graduation, 93 percent of borrowers had fallen behind on their loans, which caused interest owed to grow like festering weeds. These are people Looney agrees need to be helped—a lot.

I thought it might be instructive to look at this through the lens of one, typical, highly reputable, selective public university. As Looney’s table shows, graduates of selective public colleges and universities make up 33.7% of the total share of college debt. I’ve picked the University of Massachusetts. UMass is representative of all state universities, and, because I’m from Massachusetts and long ago was a Trustee at one of its foundations, I know the school better than, say, Penn State or Connecticut.

The UMass flagship campus in Amherst sits on more than 1,400 acres and has about 24,000 students. Out of more than 850 US public colleges, it is #68 in US News & World Report’s current rankings. Tuition, fees, room and board total $32,168 for in-state residents, about $50,000 for out-of-staters. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts currently contributes (subsidizes) 31% of the university’s total costs, or $14,287 per student, which means students’ tuition would be considerably more without that help, somewhere in the range of the cost of a selective private college, or an out-of-state UMass student. Every state subsidizes its selective public colleges to some degree.

Nationally, in 1967, 47% of high school graduates moved on to college. Seventeen percent would drop out, 15.4% white, 28.6% black. Today, less than 10% drop out; 10.7%% of drop outs are Black. We are approaching equality in that regard.

That’s where UMass is now. Fifty-five-years-ago, when I was young, things were different. Facts And Figures 1967, from the then UMass Office of Institutional Studies, is a 163-page, deeply detailed report of the university as it was then, all of it in one spot. I do not think you’d find a similar study today.

In 1967, annual tuition and fees were $336; room and board, $939, for a total cost of $1,275. The university employed 729 full-time faculty for 9,439 students. Today, there are about 1,400 full-time faculty. In 1967, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts picked up 67% of the university’s operating costs (as opposed to the aforementioned 31% today).

What you bought in 1967 for $1.00 would now cost $8.87, with a cumulative rate of inflation of 787%. Over that time, tuition, fees, room and board at the University of Massachusetts have increased by a factor of more than 24. If the tuition at UMass had just grown by the rate of inflation, it would now be $11,310, not $32,168.

So, extrapolating from current demographic and UMass data to the national picture, four things have been at work over the last 55 years. First, student costs have grown at nearly three-times the rate of inflation. Second, the state has reduced its share of student costs by more than 50%, which is representative of the nation. Third, the percent of high school graduates who go on to college has grown from 47% to nearly 62%. And fourth. wages have not even remotely kept up with the cost of college. According to the Congressional Research Service, real wages (wages adjusted for inflation), grew only 8.8%, at the 50th percentile level of all earners, since 1979.

President Biden’s initiative will likely remain a political football at least until the mid-terms, probably beyond. My own conclusion is that it will help a lot of people who need it and will be unnecessary largesse, at taxpayers expense, for those many who don’t. And it does nothing to solve the real problem.

Unless and until we can control the cost of college, this crisis will continue for future generations. College cost growth at three times the rate of inflation is unsustainable.

We need to do much more than forgive a slice of college loans. That’s like trying to save a sinking ship by tossing the first mate a rope of sand.